A temporary exhibition of In Flanders Fields Museum

27/10/2018 – 15/11/2019

SET-UP & CONCEPT

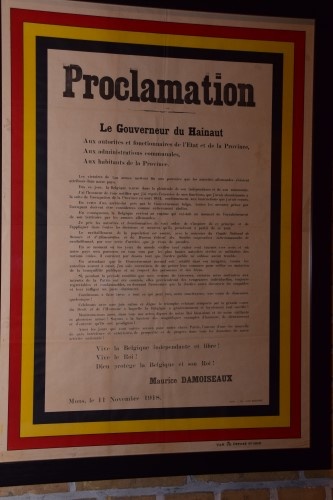

If we were to believe the communication of various events or commemorative initiatives in the run-up to 11 November 2018, the war ended on 11 November 1918, which, of course, is not true. An armistice was concluded, between soldiers, and that is not the same thing as the end of the war. The war to end all wars officially ended – at least in the west – on 28 June 1919, with the Treaty of Versailles.

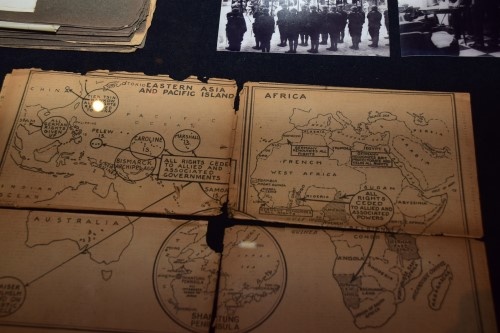

‘Versailles’ sealed the fate of Germany, and the way in which it did that, caused a lot of grief afterwards. In the meantime, in Central and Eastern Europe, several civil wars were raging between groups vying for power. In the wake of Versailles, five subsequent treaties were concluded with the 'other losers' of the First World War. The maps of Europe and the Middle East were thoroughly redrawn. Sixty million people acquired a new nationality, and twenty-five million became a minority within their own state borders.

The peace that ensued after the Paris conference, rather than end wars, would become the cause of many later conflicts. The war to end all wars would ultimately only be called ‘the First World War’. Even today conflicts are raging whose roots can be traced back to Paris 1919.

When the In Flanders Fields Museum decided to stage this exhibition, its curators faced at least two major challenges:

- How do you broach such a complex subject and integrate it into an exhibition in a historically accurate manner?

- How do you show the gigantic impact of the First World War and its aftermath, on people?

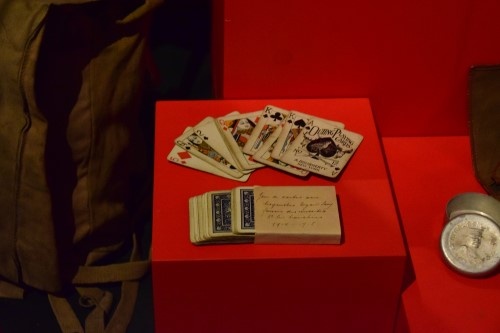

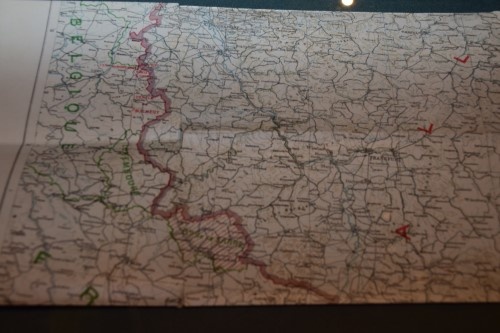

The answer to the first challenge arose from the design. Clearly, maps were going to play an important part in this exhibition. However, the winning concept by Tijdsbeeld & Piece Montée draws the map out of its comfort zone and plays with various presentations and interpretations. This is where the designer introduces his strongest asset: the metaphor of the table. A family eats, lives and talks at a kitchen table, together. A destroyed table can be an orphaned reminder of war’s violent passage. A negotiating table is where negotiators, peacemakers, warmongers and cartographers come together to negotiate a new world order. The colourful table plan of the Treaty of Versailles is a perfect metaphor for the range and versatility of how the world war was settled in 1918. Finally, there’s the table as a gaming board, not with Risk pawns, mind you, but with real persons and peoples. In many cases the table served as a drawing table, pushing people to live on this side or that of a border at the whim of a red pencil line. In line with this vision four large tables make up the four anchor points of the exhibition: a destroyed table (the Final Offensive), an abandoned, laid kitchen table (the Baccarne family), the U-shaped negotiating table in Versailles (the Treaty of Versailles) and a huge board game table (the remaining treaties).

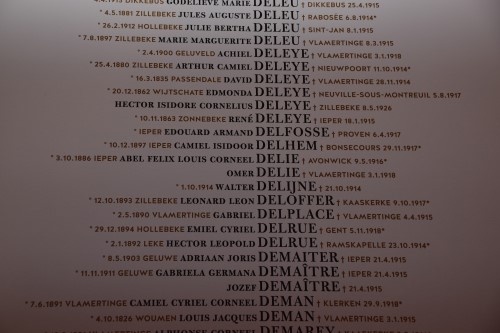

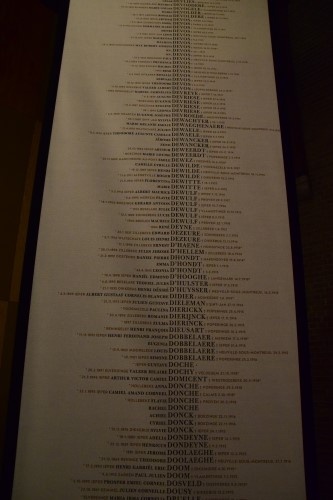

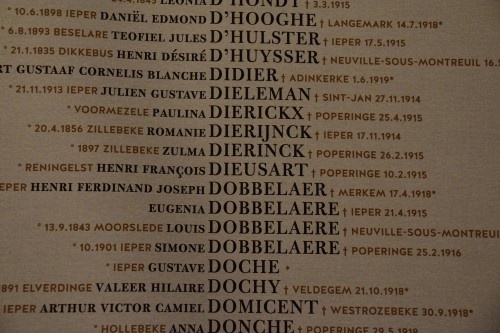

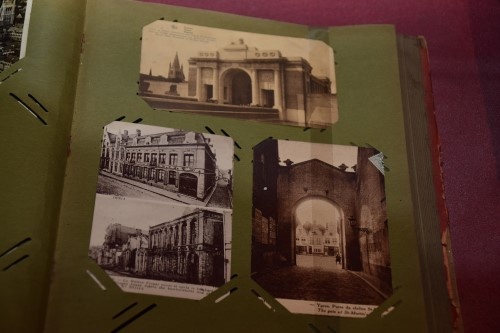

To tackle the second challenge, the In Flanders Fields Museum falls back on its basic principle: the measure of war is man. At all times, the museum scenography pivots around the human experience of all those involved, both civilians and soldiers, victims and relatives from the countries concerned, during and long after the war. In this exhibition their voices can be heard on many levels: from civilians and soldiers who actually lived through the Final Offensive, via a wide-ranging and multi-layered family story from the Westhoek and the fate of ‘new Belgians’ in the East Cantons, to an international mix of voices who can only observe the consequences of the aftermath of the war. By way of a coda we pick up the thread of the family story, but we also confront the visitor with another consequence of the war: dealing with the human loss. After the war, monuments to commemorate and honour the dead were erected all over Europe. The names of many, mainly civilian, casualties, however, were never carved into a monument, and so, were forgotten on commemorative occasions. Ieper is certainly a case in point: until recently, its tragic war years had prevented any thorough record of the city’s civilian casualties, which might also explain why there is no monument to remember them by name to this day. This exhibition sets up the beacons for a monument that was never built ...

To End All Wars? puts the cards, or rather, the maps on the table. The maps of the war, the ultimate battles leading up to the Armistice, and the maps of the new world order that followed. Age-old empires vanished, and new countries emerged on paper. Lines on maps would henceforth determine the new future of millions of people. As the war had so often demonstrated, those lines would mainly serve to dash the hopes of many people.

The (re)assessment of a world war is on the table(s) here. By telling the story of some (one family) and a few people (victims from Ypres and East Belgium) we recount the fate that befell millions around the world.

BIRD’S EYE OVERVIEW OF THE EXHIBITION

TABLE 1

The Final Offensive / The Final Advance in Flanders

After a spring of German attacks, the tide turned in the summer of 1918. The French, supported by the Americans, launched the counterattack at the Marne. The British armies attacked in the Lys valley on 5 August and, alongside some Australian and Canadian divisions, at Amiens on 8 August. In the north, Bailleul and the Kemmelberg were recaptured in the course of August. The final offensive was launched on 28 September 1918, with King Albert commanding a force of Belgian, French and British troops. The first, successful day (28 September 1918) would also turn out to be the bloodiest in the history of the Belgian army.

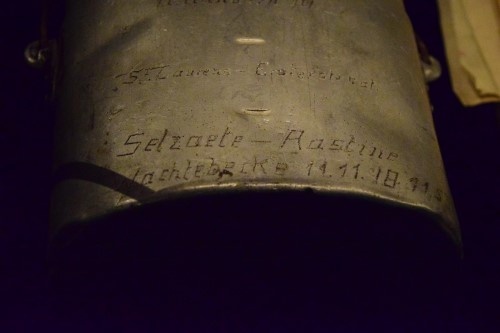

In a second phase, French divisions took over the centre of the Allied offensive. During the last phase, which started at the end of October, two American divisions joined the fray. The Belgian Army steadily advanced between Roeselare and the coast. The battles were hard and in the areas that had not seen fighting before, many civilians got caught in the crossfire. By the 11th of November, the allied armies had reached a line that stretched from Zelzate, over Ghent, Oudenaarde and Ath to Mons. At least 35,000 people died during the final offensive in Belgium, including over 2,400 civilians.

TABLE 2

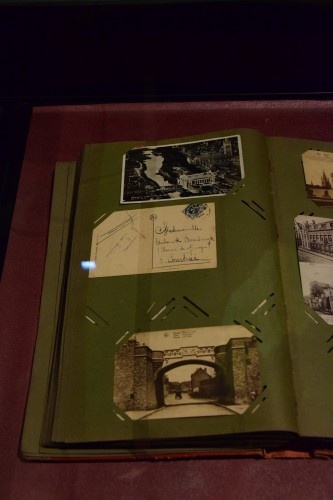

The line that dashed the plans of the Baccarne and Deschepper families

Military history has its fair share of lines on maps. Well-known and important, they rarely amount to anything good. In the Westhoek, the frontlines of the First World War marked the fate of millions of people forever. This was the case for both the soldiers who came here from all over the world, and the local population who lived and worked in the villages and fields that were turned into battlefields.

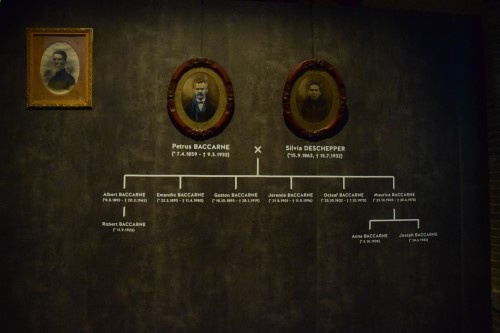

On the evening of 20 October 1914, the front line between the German troops and the French and British troops came to a standstill north of Langemark, between the farms of the Baccarne and Deschepper families. The families of the parents and brothers of married couple Petrus Baccarne and Sylvie Deschepper found themselves on the Allied side of the front line. Petrus, Sylvie and their six children were stuck on the German side. The line tore the families apart, leaving an indelible mark on all of their futures, to this very day.

In the film, some second-generation family members testify about their families’ war, in Belgium and in France.

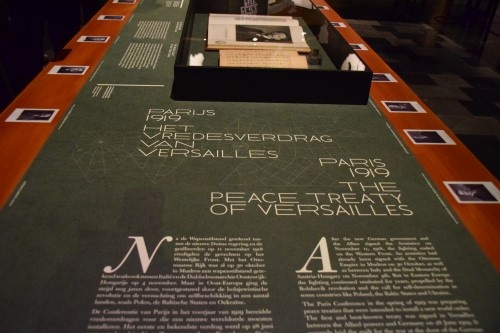

TABLE 3

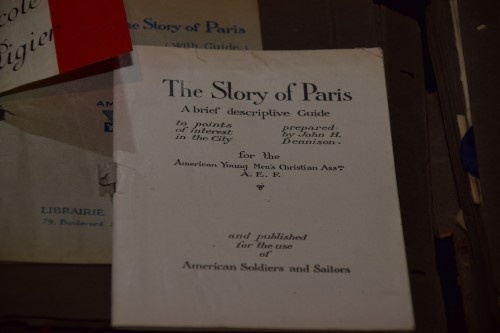

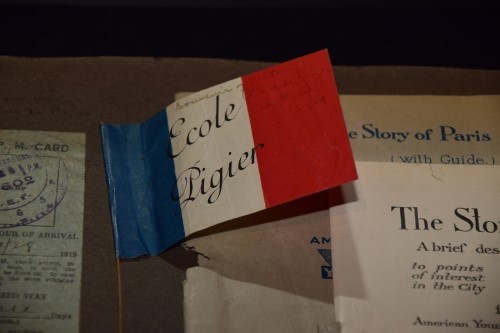

Paris 1919, the Peace Treaty of Versailles

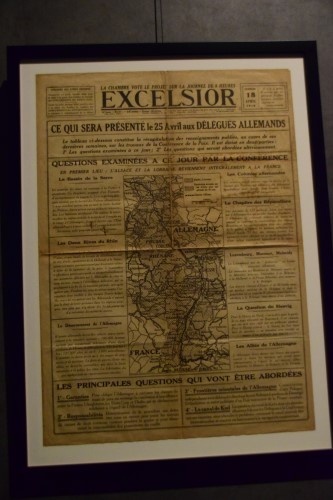

After the new German government and the Allies signed the Armistice on November 11, 1918, the fighting ended on the Western Front. An armistice had already been signed with the Ottoman Empire in Mudros on 30 October, as well as between Italy and the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary on November 4th. But in Eastern Europe the fighting continued unabated for years, propelled by the Bolshevik revolution and the call for self-determination in some countries like Poland, the Baltic States and Ukraine.

The Paris Conference in the spring of 1919 was preparing peace treaties that were intended to install a new world order. The first and best-known treaty was signed in Versailles between the Allied powers and Germany on 28 June 1919. It squarely laid the guilt for the war at the door of the German Empire, forcing it to make full reparations. Parts of the old empire and its colonies were assigned to other countries and the army was forced to disarm. From now on, international conflicts would be resolved by a - yet to be established - League of Nations.

The US, which had presented itself as the architect of the new world order with President Wilson’s Fourteen Points, would ultimately not join the League of Nations.

TABLE 4

Towards a new world order by 1924

The Treaty of Versailles was soon followed by similar treaties with the other Central Powers. They too joined the League of Nations, were given full blame and lost considerable territories.

The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, on September 10, 1919, between the Allies and Austria, was followed by that of Neuilly, between the Allied Powers and Bulgaria, on November 27, 1919.

The Treaty of Trianon, between the Allied Powers and Hungary, could only be signed on June 4, 1920, after the Hungarian Revolution of March 1919.

The treaties led to the creation of the new states of Czechoslovakia and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which would later become Yugoslavia.

The Ottoman Empire was tackled in the Treaty of Sèvres of August 10, 1920. It confirmed British and French colonial power in the Arab territories and their control over the Dardanelles. European Turkey was reduced to a strip near Constantinople (Istanbul). The claims of Greece and Italy heralded a revolution in Turkey, which brought Kemal Atatürk to power in 1922. Bringing stability back to Turkey, he negotiated a new treaty, ratified in Lausanne on July 24, 1923. It put an end to Turkish reparation payments and returned the zone near Istanbul, Gallipoli and Izmir under Turkish rule.

In December 1922, the Russian civil war led to the formation of the Soviet Union which was internationally recognized in 1924. More than five years after the end of the Great War in the west, a new world order was finally established.

CODA – LEGACIES OF THE WAR

Coda 1: A monument that was never built

After the war, monuments to commemorate the dead were erected in all the countries that had been involved. Identifying the war dead turned out a more difficult proposition than coming up with an official commemoration discourse. Across the country, monuments sprang up that glorified ‘our heroes’. For military personnel, the accolade was practically a given. For civilians, however, much less so. In 1918, in Belgium, what constituted a civilian casualty of an armed conflict hadn’t even been defined, explaining why only a small proportion of civilian casualties had been included in official commemorations.

In frontline towns like Ypres the mapping of civilian casualties proved very challenging. The chaotic circumstances and mandatory evacuation of civilians had erased many traces. After the war, the city just could not figure out who its civilian casualties were - a scenario repeated after WW2 - meaning that, to this day, Ypres could not commemorate them by name. With the inclusive Names List, however, all civilian casualties who either originated from or died in the city’s districts will be united with the military dead from those very places. With the help of civilians today, the unbuilt monument to these victims is erected here and now.

Coda 2: A war that never ends

The front line that had torn apart the Baccarne and Deschepper families in Langemark-Poelkapelle in October 1914, is leaving its mark to this day. The branch of Petrus and Sylvie Baccarne, who spent the war in occupied Belgium, only returned to their region in 1922, a damaged family. Petrus had become an old man, with one son dead and two others invalids of war. With agricultural work proving impossible, they were forced to take up different occupations. Two brothers became cobblers.

The branch of the family that had spent the war as exiles in France decided not to return. The reports about the former home front were ominous: the country had been utterly destroyed and, in their eyes, offered no future at all. The ‘abandoned’ fields of French farmers killed in the war seemed to hold the promise of a better future. And so, the Deschepper family settled in Normandy for good. They became French.

Generation upon generation, the Flemish and French branches kept in touch. In doing so, they have remained conscious of the legacy of the war to this day.

In this film, some second-generation family members testify about how they deal with their families’ war, in Belgium and in France.

FUTURE

A pivotal exhibition for the In Flanders Fields Museum

During the ‘2014-2018’ centenary commemoration, the choice of subject matter for IFFM’s temporary exhibitions was governed in large part by the historical calendar of a hundred years ago. Logically, IFFM staged exhibitions on the big battles that had taken place around Ieper. After 2018, IFFM regains the freedom to set up major thematic exhibitions, independent of symbolic birthdays or specific regional impulses. Looking forward to 2019-2023, IFFM will highlight the broad aftermath of the First World War and how people and countries rebounded from and dealt with it, both regionally and internationally. As things stand, the war’s lasting consequences can be felt to this day, even after the centenary commemoration. Our purpose is to conduct a constantly updated and post-national dialogue about war and peace that can serve as a globally inspiring example.

In line with that vision, To End All Wars? is a pivotal exhibition that bridges the gap between a historical (the centenary commemoration of the Final Offensive) and a thematic (the far-reaching effects of the First World War) exhibition. In the years ahead, IFFM will develop a programme of major temporary initiatives with an international scope, tackling the war’s aftermath and how countries and people dealt and coped with it. Exhibitions on the Reconstruction (2020) and the First World War in the Middle East (2022) are already on the cards.

Education

In the future, the IFFM’s educational aspect will only become more important. In the years to come, the memory and peace education of the museum and city will be constantly updated in close cooperation with Ieper Vredesstad (Ieper, City of Peace). IFFM helps guarantee the intangible heritage related to ‘Commemoration, remembering and the idea of peace'.

This exhibition harbours enormous educational potential, both conceptually and in terms of its contents. If there is one thingTo End All Wars? wants to make abundantly clear, it is that history is always about people, and about processes in which people are involved. Processes which determine these people’s fate, often against their will. And that the burden of that history can be carried over from generation to generation. For these reasons, the past should be approached with the aim of recognizing, discovering, and learning from mechanisms to stop making the same mistakes as in the past, or to at least better understand the attitudes of some parties today.

To End All Wars? suggests plenty of connections between Paris 1919 and the present day. In the course of 2019, IFFM’s Educational Services will develop an educational package based on the personal stories and the map of the new world order (table 4). By confronting young people with choices that had to be made then (as now), this educational package aims to instill them with a critical view and a nuanced assessment of war and peace.

COLOFON

- Curators: Piet Chielens en Pieter Trogh

- With help from the Research Centre In Flanders Fields Museum: Birger Stichelbaut, Dominiek Dendooven, Annick Vandenbilcke, Dries Chaerle, Frederik Vandewiere, Jan Dewilde, Lynn Maelfeyt, , Virginie Deroo, Filip Deheegher, Wouter Sinaeve, Ann-Sophie Coene, Sien Demasure, Lars Op de Laak

- Many thanks to: Aline Thomas; Els Herrebout (Staatsarchiv Eupen); Gert De Prins (Algemeen Rijksarchief – DAO); Dr. Herbert Ruland, Carlo Lejeune, Alfred Rauw en Wilfried Jousten; Inge De Bruyne en familie (schenking Valère De Boodt); Marie Saey en familie (schenking Edgard Saey); René De Clerck; Technische Dienst Stad Ieper.

- Design and scenography: Janpieter Chielens, Lisbet Cools, Rik Jacques, Henryk Virabian / Tijdsbeeld & Piece Montée

- Realisation: TWIN design, Printville, Bel-Arte kaders, kaders D’haene

- Technical Applications: Ivan Claerebout

- Media: Filip Martin & Fijne Beeldwaren

- Translations: Marc Hutsebaut (English); Akira Translations (français & Deutsch)

- Loans: Algemeen Rijksarchief – Archief Dienst Oorlogsslachtoffers; Anna Baccarne; Dirk Vandekerckhove; Joseph Baccarne; Kathy Holvoet; Mireille Lieutenant; Philippe Oosterlinck; Sint-Andriesabdij Zevenkerken;

A number of pictures taken during the press presentation on Friday, 26 October 2018.

Page made by Tekst: IFFM / Foto's: Filip Van Loo.